How labeling children stunts their natural development.

As the author of The Enneagram World of the Child, I want to be clear: I am not in favor of typing children.

While my book explores how personality begins to take shape in early life, it does so by examining the family ecosystem—the relational field, the emotional atmosphere, the unconscious patterns, and inherited beliefs that influence the child’s emerging sense of self. The focus is not on placing a child into a type, but on understanding how the parents’ personality, wounds, and expectations shape the developmental soil in which the child is growing.

Children are not born with a type. They are born with presence, essence, and possibility. Personality comes later—an adaptation, a strategy, a response. And if we rush to label the child before they have even had the chance to discover themselves, we not only limit their development, but we also project our unresolved narratives onto their unfolding identity.

This article is about the quiet danger of that projection. It’s about what we lose when we seek definition at the expense of wonder. It’s about why parenting is not a process of defining, but of witnessing. Not a management project, but a devotional practice of awe.

Hidden Harm in Good Intentions

There’s a quiet violence we don’t speak about—a violence wrapped in good intentions, cloaked in the language of insight, and delivered through online quizzes, well-meaning books, and parental anxiety.

It begins with a question that sounds innocent enough: “What type is your child?”

From the moment we ask this, the child is no longer simply becoming. They are being defined.

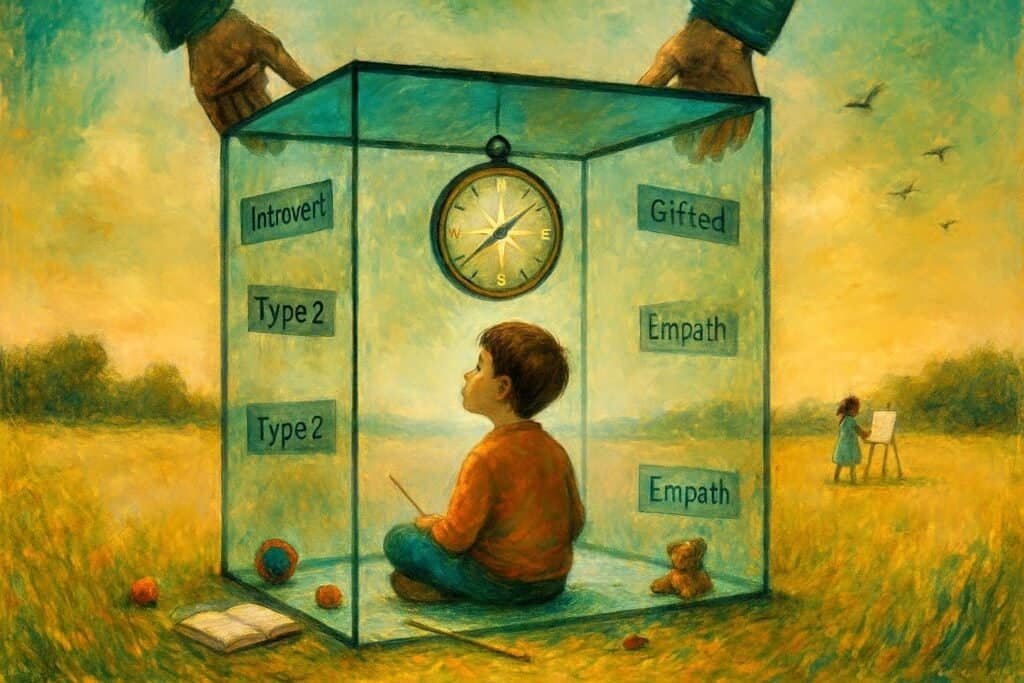

We live in an era obsessed with categorization. Personality types, learning styles, Enneagram numbers, MBTI codes, even animal archetypes—the seduction of sorting is everywhere. The child, fluid and emergent, is subjected to frameworks designed to predict, explain, and optimize their development. But in doing so, we may unknowingly perform a kind of epistemic violence: transforming the living poetry of a child’s becoming into a checklist of traits and functions. The mystery becomes a management problem. Wonder becomes a worksheet.

So we must ask: Do you want to raise a child of wonder and awe, or a label?

The Seduction of the Label

Parents, educators, and even psychologists often justify early typing by pointing to its benefits, including self-awareness, tailored education, and improved communication. And yes, when approached with subtlety, developmental awareness, and clear ethical boundaries, temperament studies can offer valuable insights into individual differences. But insight is not identity. Observation is not ontology.

The problem is not observation but ossification. Labels stick. Not because children are static, but because adults are. Once a label enters the room, it defines not just the child, but the field of possibilities. We see what we expect. We reinforce what we name. The “introvert” is praised for reading quietly. The “leader” is chosen to go first. The “sensitive child” is protected from challenge.

This is what researchers call reification: the process of transforming an abstract concept into a tangible thing. A child is not born with “extraversion” or “Type 4-ness.” They are born with potential—possibility waiting for context, environment, and time. But labels, especially in childhood, interrupt this dance.

Labels as Self-Fulfilling Prophecies

Once labeled, a child adapts to the expectations around them. If they are “shy,” they begin to speak less. If they are “strong-willed,” they become oppositional. And if they are praised for being “clever,” they may fear failure, avoiding challenges to preserve the identity that earned them approval.

Even the so-called “positive” labels backfire. A child labeled as “gifted” might stop taking risks, afraid that any mistake would disprove their intelligence. A “natural leader” may feel pressure to perform, suppress vulnerability, or reject collaboration. Labels create performance. And performance is the death of spontaneity.

This is not theory. It’s well-documented. The Pygmalion Effect, where teacher expectations shape student performance, demonstrates the power of belief to influence outcomes. But what happens when the belief is encoded in a personality label?

Projection and Living Through the Child

Beneath many of these well-intentioned labels lies something unspoken—an emotional echo from the parents’ lives. Unresolved ambitions, wounded dreams, and unmet longings often slip beneath the radar of conscious awareness and reappear in the child, dressed in new clothes. A mother who never felt heard might eagerly affirm her child’s “communication strengths.” A father who never achieved the dream of being an artist might see his child’s early scribbles as the first signs of “creative genius.” What begins as pride can quietly harden into a role.

This is parental projection: the subtle, unconscious transference of a parent’s interior world onto their child’s unfolding self.

But projection doesn’t stop at recognition. It bleeds into expectation. The child becomes a stand-in for the unlived life of the adult. The label becomes a script. “She’s so mature for her age” becomes a hidden request: “Please be the adult I never got to be.” “He’s a little philosopher” becomes a yearning: “Please make meaning of the chaos I couldn’t bear.”

These projections are often infused with love, but a love entangled with need. The child is not loved for who they are becoming, but for who they appear to redeem. And when parents begin living through their children’s achievements, identities, or perceived strengths, the child becomes a mirror, not a mystery.

This dynamic often hides behind the language of empowerment:

- “We just want to support her gifts.”

- “We want him to get the chances we never had.”

- “She’s going to be amazing at [insert parent’s unfulfilled dream here].”

But beneath that language is a subtle control: the child is being asked to carry what is ungrieved, unresolved, or unfinished in the adult.

The danger is not just that the child is mis-seen, but that they are unseen altogether.

Living vicariously through a child is not simply about control; it’s about collapsing the boundary between two lives. It’s about inserting oneself into the space where the child should be discovering their rhythms, their timing, and their direction. In such cases, even the child’s rebellion becomes part of the parent’s script—a reversal still tethered to the same expectations.

And yet, the great paradox is this: the more we try to script our child’s becoming, the more we interfere with the very wonder we hope to protect.

Children Are Not Ready to Be Typed

Here’s what the science tells us: typing children is premature, inaccurate, and harmful.

- Neurologically, the brain isn’t fully developed until around age 25. Systems governing self-awareness, impulse control, and emotional regulation are still under construction.

- Developmentally, children often exhibit traits from multiple types within a single day. What appears as “introversion” may simply be fatigue. What we call “structure-loving” could be trauma masking as preference.

- Scientifically, tools like the MBTI and many popular typing systems lack reliability and validity in adults, let alone children. Up to 50% of adults change their “type” after just a few weeks.

Mistyping children doesn’t just mean we misunderstand them; it also means we fail to appreciate them. It means we guide them into a life built on a misunderstanding. We replace their fluid, unfolding nature with a static self-concept. And the worst part? We call this love.

From Curiosity to Control

What drives this urge to type? At its core, it is fear.

We want to know our children. We want to help them. But we also want to predict them. Typing offers a feeling of control. It transforms the unknowable into the known. But that control often comes at the cost of connection. Instead of meeting the child in the moment, we project a system onto their being. We stop seeing them and start seeing a “profile.”

This is what developmental psychologists refer to as psychological control disguised as understanding. It’s not malicious. But it is manipulative. When we say, “You’re doing that because you’re a Type 5,” we’re not understanding the child—we’re interrupting their process of discovering themselves.

This is the great irony: we label to understand, but in the process of labeling, we lose the child. Understanding becomes projection. Presence becomes programming.

What Are We Losing?

When we type children, we don’t just risk limiting them. We risk losing the very qualities that make childhood sacred: wonder, curiosity, imagination, spontaneity, and resilience.

- Wonder is the foundation of learning. Aristotle said philosophy begins in wonder. Children are born philosophers, asking “Why?” with radical sincerity. Labels replace why with what. “What type am I?” becomes more important than “Why do I feel this way?”

- Free play, which fosters creativity and emotional intelligence, is increasingly replaced with structured assessments and adult-imposed categorizations.

- Creativity, research shows, suffers from early social labeling. The infamous “fourth-grade slump” corresponds with increased social pressure and decreased willingness to take risks—traits directly linked to over-identification with external expectations.

Children need space to try, to fail, to explore, and to learn from their mistakes. Personality typing, especially when imposed early, narrows the field of play. It reduces possibility to prediction.

But What About Temperament?

There’s a subtle but crucial difference between temperament and typing.

Temperament refers to observable patterns of energy, adaptability, and mood. It’s a loose sketch, not a fixed identity. When used appropriately, like in Thomas and Chess’s Model, it can help parents tune in to their child’s rhythm. But temperament is a directional cue, not a destination.

Even then, the goal is not to categorize but to create what researchers call goodness of fit—adjusting the environment to support the child, not the other way around.

In contrast, personality typing, especially when it relies on rigid categories like MBTI or Enneagram, often becomes an act of definition. It tells us who the child “is.” And that’s the danger.

What the Enneagram Teaches Us—If We Listen

Ironically, even the Enneagram—a system that warns against identification—has been misused to type children. Most master teachers advise against using the Enneagram for anyone under the age of 18. Why? Because what we call a “type” is often a defense mechanism born from wounding, adaptation, and experience. Typing a child is like measuring the depth of a river while it’s still forming.

The real message of the Enneagram is this: your type is not who you are, but who you believed you had to be. Typing children risks giving them the very wound the system was designed to heal.

Epistemic Humility and Developmental Trust

When we talk about raising children of wonder, we’re really talking about epistemic humility—the willingness to not know, to not label, to witness rather than define.

Developmental psychologist Kurt Fischer reminds us that “well-being is the degree to which potential is being realized.” Not predicted. Not sorted. Realized.

And potential unfolds in relationship. The child becomes through interaction—through play, frustration, joy, exploration, and repair. Not through assessment.

To truly raise a child of awe, we must be willing to stand in awe ourselves. To say: I don’t know who you are yet. I won’t pretend to. But I’ll be with you while you find out.

A New Kind of Parenting Posture

So what does it look like to raise a child of wonder rather than a label?

It means:

- Listening more than interpreting.

- Observing without overlaying frameworks.

- Letting your child surprise you.

- Praising effort, not essence (“You worked hard,” not “You’re so smart”).

- Allowing for change—even reversal.

- Asking open-ended questions instead of offering answers.

It means protecting unstructured time. Trusting in boredom. Valuing the slow unfolding over the quick fix.

Most of all, it means seeing your child not as a problem to be solved, but as a mystery to be witnessed—a being in the process of becoming.

Holistic and Emergent Frameworks

Thankfully, there are developmentally appropriate approaches that respect the child’s fluid nature:

- Dynamic Systems Theory views development as non-linear and adaptive, unfolding through interactions between inner potential and outer environment.

- Neurodiversity frameworks emphasize variation as natural, rather than deficient, and call for supporting individuals rather than fixing them.

- Strengths-based assessments focus on what the child can do, loves doing, and naturally gravitates toward, offering guidance without restriction.

- Child-centered education adapts curriculum to individual learning rhythms without prescriptive expectations.

These approaches do not deny difference. They just refuse to turn difference into destiny.

The Most Radical Act: Let Children Be

In a culture addicted to measurement, typing, and optimization, perhaps the most radical thing we can do is refrain from categorizing our children. To resist the metrics. To pause before naming. To trust the invisible.

To say:

- I see you.

- I don’t need to explain you.

- I will protect your mystery.

Children do not need to be fixed, defined, or explained. They need to be met—with presence, awe, and respect.

Let us not type them. Let us tune to them.

Let us not funnel them into identities. Let us follow them into possibility.

Let us not raise labels.

Let us raise humans—wild, beautiful, becoming humans.

A Question Worth Holding

The next time you feel the urge to type, sort, or name your child’s personality, pause.

Ask instead: Am I seeking to know them—or to manage my own uncertainty?

Then ask: Am I seeing my child—or projecting myself onto them?

And finally: What might happen if I just let them be?

Because in that space between not knowing and not needing to know, wonder is born.

And perhaps that is the greatest gift we can give.

Invitation to the Dance of Development

If you’re ready to go beyond labels and explore the deeper emotional forces shaping your relationship with your child, The Dance of Development offers a starting point.

This 8-week course offers insight and understanding into how your patterns influence your child—and provides a way to create more space for them to be themselves, free from parental need and projection.

John Harper is a Diamond Approach® teacher, Enneagram guide, and a student of human development whose work bridges psychology, spirituality, and deep experiential inquiry. He is the author of The Enneagram World of the Child: Nurturing Resilience and Self-Compassion in Early Life and Good Vibrations: Primordial Sounds of Existence, available on Amazon.